It was March 2020, in a pre-quarantine Barcelona, when I applied for a PhD program. I had a hunch. An intuition based on two main contemporary trends.

For some time now, our parties, events, social networks and flyers are all aesthetically represented with computer generated image (CGI), volumetric/3D renderings, digital modelled designs and video-game environments. They suggest alternatives to our daily reality: possible worlds, speculative bodies, new interspecies relations, fairer social distributions and more “livable” lives against social and planetary crisis.

They are all involved in an aesthetic “zeitgeist” of change. The possibility-of-another-world. The imagination-of-another-reality. The performative semiotic-material possibilities of something radically new. Another-future.

Parallel to the aesthetic boom of volumetric CGI, our conferences, journals and publishing houses… are all starring in another current trend: they are recovering the feminist sci-fi traditions from the seventies on. Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ… are being republished, praised and discussed. We are mainly interested in how they used sci-fi literature in order to make worlds far away from our coercive sex/gender system. Worlds where violent rules were stretched or smashed, opening up different options of emancipation.

My intuition then entangled these two aesthetic-cultural-political tropes. CGI volumetric images, video-game environments, 3D virtual worlds: all of them, the feminist science-fiction of today. The contemporaneous queer world-making. The revival of the utopian creativity. The current aesthetic tools serving the shaping of better political alternatives.

Then the quarantine arrived.

Sadness, uncertainty, panic. The impossibility of just thinking about tomorrow, and our post-pandemic social relations.

We cancelled the future.

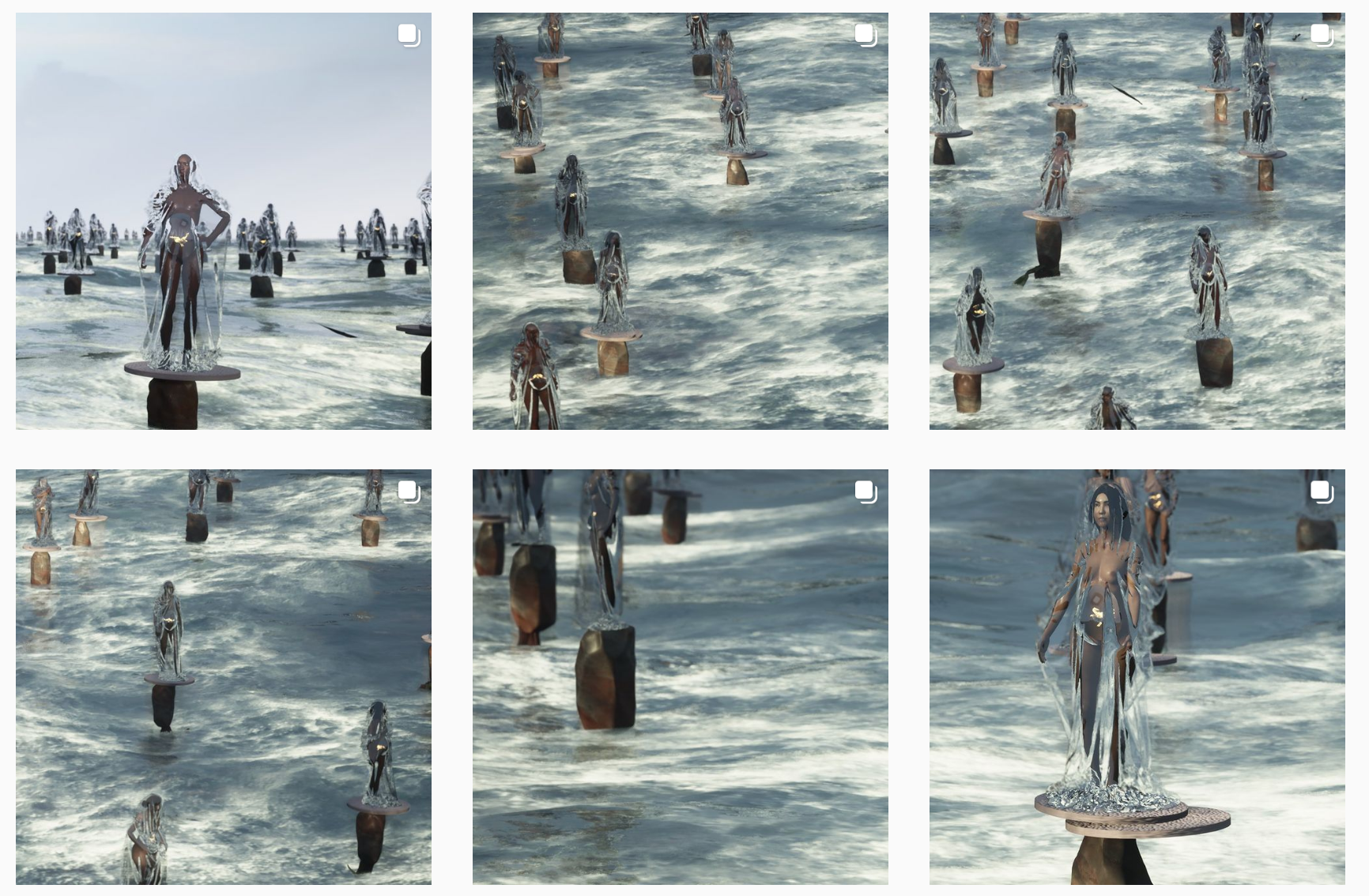

After a strange summer, oasis in the middle of the fire, September finally arrived. Under the shadow of an uncertain second wave, the cultural agenda was reactivated. In Barcelona, electronic music and visual arts festival MIRA started a series of immersive screening in IDEAL, Poblenou’s newest centre of contemporary visual culture. MIRA.mov opened with “We are at the end of something”, by Keiken, Ryan Vautier and Sakeema Crook. A film that imagines a post-Covid world, reflecting on its tensions and possibilities.

My intuition came back immediately.

“We are”, indeed, “at the end of something”. And imagining what will come afterwards. From this crossroads of time and speculations, CGI artists are modelling alternatives, building up virtual possibilities toward better futures. Furthermore, “We are at the end of something” proposes a transfeminist future. And the starring figures of the film carry in their crystal bellies objects and beings, in a direct allusion to Ursula K. Le Guin’s carrier bag theory.

Contemporary volumetric CGI practices dialogue with feminist science-fiction from the seventies, and they have common interests. Immersed in the film/carrier bag, on September the 10th 2020, my intuition was urgently alive: she was beating, full of significance.

Unlike hunting, Le Guin’s carrier bag theory is focused on the recollection of vegetables: leisurely, without heroes, nor epic stories. Fiction can be retold from the recollection too. From the accumulation of details, from a collective and shared narration.

And now, with my revived intuition, I find myself inside the bag. Here, contemporary volumetric CGI aesthetic is entangled with transfeminist science-fiction. And in this compost of semiotic-material seeds, we also find some of the other main challenges of our present: xenofeminism, the future, utopias, accelerationism, post-humanism, and, of course, antispeciesism.

And the recollection goes on.

spanish

Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetics?

Can we think about an aesthetic free from all forms of violence? Can we imagine an aesthetic which, even momentarily, represents and emancipation? Do radical aesthetics exists? Aesthetics which, during a tighter or wider term, found themselves in a free space outside the (aesthetic) system?

I’m thinking about this questions while reflecting about the emancipatory possibilities of aesthetics. Between the perhaps naive confidence in its transformative capacity and the perhaps conservative nihilism of the impossibility-of-an-outside to neoliberalism. Mark Fisher invites us to think that there is, indeed, a future without capitalism. And Haikim Bey affirms that there are, there were, and there will be space-time places of free emancipation, which he calls Temporarily Autonomous Zones (TAZ).

I repeat, therefore, my opening question: do Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetics (TAA) exist? And better: are we interested in this category in order to make the norm unstable, to think and create fairer alternatives, better future speculations, through aesthetics? As an example: solarpunk. A trend which involves literature, architecture, video-games, among others, and uses bright colours, floral motifs, art nouveau… in order to build up a luminous future of renewable energy, planetary well-being and social justice. Is, then, solarpunk, a Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetic?

Haikim Bey will disagree using his theory as a comparative standard. If TAA exist, or not, and if we want to use them, or not, is a decision that belongs, exclusively, to our political and ethical objectives. It is not a matter of previous intellectual reflection. However, if I go back to Bey is to think about how we can develop actual TAA, and how to critically analyse them.

To begin with, an aesthetic will be Temporarily Autonomous only when it doesn’t last long. It will

be extraordinary, or, as it commonly occurs, it will last radical until it gets absorbed by the neoliberal dominant discourse. With this in mind, does solarpunk stoped being Temporarily Autonomous when it appeared in a TED talk?

Autonomy is also counter-discourse. A Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetic will attack, as the pirate or rave spaces described by Bey, the capitalist mono-world configuration. Colours, brightness and solarpunk motifs defy the neoliberal criteria of extraction, accumulation and waste, although they perpetuate those of techno-positivist progress. In any case, solarpunk proposes unachievable worlds within the capitalist logic.

Moreover, a Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetic must be spontaneous, and spontaneously diverse. It has to appear due to common interests and passions from heterogeneous and different subjectivities. It must attack like a guerrilla, and then disappear. Solarpunk, as well as other aesthetic-philosophical trends of our century, was born precisely this way in virtual forums and social media. Bey conceives the web as a necessary tool for TAZ, but his strict definition of Zone as an IRL (in-real-life) place, stoped him from understanding the subversive potential of autonomous online spaces.

The quick extinction of an aesthetic trend is quite rare and still to explore. And it seems a sine qua non condition towards a Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetic. Lastly, Bey systematically rejects thinking about TAZ as an artistic creation. However, the autonomy of the term is also the autonomy to contradict its creator, as well as its mutation into diverse theoretic-political transformative proposals.

Perhaps solarpunk was once a Temporarily Autonomous Aesthetic, but I dare to affirm that it is no longer one. We have now a pending and constant task: to entangle diverse interests into an autonomous aesthetic that attacks the system, and immediately hides to prepare the following assault.

Photographing the crisis of the real

I am thinking about two recent scientific photographs which lead us directly towards a crisis of the real.

The first image of a black hole is one of them. It was obtained on April the 10th 2019 after two years of international work and one petabyte of collected data. Rather than a traditional photographic shooting, pressing the trigger and registering the light on a chemical screen or a pixeled net; the first image of a black hole is the result of complex algorithmic calculations, modelling proofs and virtual tests.

For the idealistic tradition, the realism of an image is inversely related to its mediation level. The more the human manipulation of the photographic machine, the less realistic the imagen will be considered. Considering this, can we talk about the black hole image, virtually and mathematically modelled through algorithmic calculations and computational tests, as a realistic image? The represented black hole, is it real?

Furthermore. The centre of a black hole is still scientifically unknown. Consequently, the mathematical models employed by the scientists couldn’t virtually predetermine how the black hole interior will look like. The image, then, doesn’t show an answer. Rather, it certifies that we still don’t know. Thus, the representation of an ignorance, is realistic? Can we consider knowledge the photographic proof that we do not know? It is realistic a picture of the emptiness?

The second picture that lead us to the crisis of the real is the result of the interference experiment, one of the most known empirical experiments of quantum physics. I don’t have enough space here for the details. In general terms, the experiment follows photon particles through the space, crossing small apertures and finally impacting on a screen that acts as a photographic plate. The results empirically show that photons come towards the plate from simultaneously multiples places, i.e., photons potentially exist in several different places at a time. Only when hitting the plate, they are fixed in one singular position in within the diverse possibilities. The observation and measurement apparatus, the observation and the measurement themselves, limit the heterogeneous potential of the quantum reality.

I am particularly interest in the photographic plate hit by the photons. Following idealist realism, photons exist precisely there where the photography registers them. However, the experiment proofs exactly the opposite. When an image is the evidence that reality exists differently to what is determined by the image itself, is it realistic? When a photograph is the irrefutable test that reality exists differently to what is printed on the photograph, which veracity criteria should we apply?

Digital images are socially praised for their realistic capacities, for how they emulate the standards of what we believe as real. Publicity and journalistic discourses from FX effects and videogames industries praise their capacity to mirror textures, illumination and movement with phot-realism. Nevertheless, after the black hole image and the quantum photons experiment seems even impossible to write photo and realism together. They have become an oxymoron.

The social response to an unreal image is often a collective phobia and fear to be manipulated or cheated. On the contrary, there are alternative and creative genealogies which, instead of praising the perfect duplication of the real –which is, precisely, the normative– they encourage the imaginative. Decades of feminist science-fiction, Afrofuturism and queer world-making coincide in their rejection of reality as a violent space, as well as in the creation of better and fairer alternatives. Through their works we can find new philosophic and political tools of anti-realism, potentially useful to face the contemporary image.